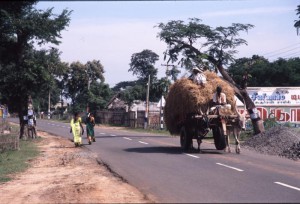

The production line of the Hero is the biggest in the world, spitting out six million bicycles a year. You probably won’t find one in your local bike shop, however for those that have travelled to India, they are a ubiquitous sight, providing the short-haul transportation of India’s vast working class. I left my range of expensive, multi geared and multi compositioned bicycles in New Zealand, and went there to see what all the fuss was about.

I bought my Hero in Kathmandu, allured by its shiny white and green paintjob, gleaming cromoly handlebars and its vast array of included accessories. The complete package came with long curving mudguards, a solid looking rear carrier, high decibel bell, fully enclosed chain-guard, built in wheel immobiliser and a suitably strong stand that could support its rather hefty bulk when not propelling me through the countryside. Did I mention the price? NZ $70, brand new. I added on a front basket to hold my important documentation and camera, and I was ready to go.

The vague plan had been simply to strap on a pack and cycle to Cape Comorin, the very southern tip of India. Bar the bike, the only actual cycling specific gear I had, was an ageing pair of Double Happys… to soften the blow on the bumpy roads. The biggest challenge initially was getting to the northern half of India via Nepal, over the Himalayers on the heaviest bike I have ever owned, with a single, knee bending, 68 inch gear. Over the next month I struggled my way through the poorest states of India – Bihar, Jharkand and Orrisa, poverty becoming ingrained into me as a mere normality. Eventually, I was joined by my girlfriend, Tina, in Bangalore. From there, we set out together into the insipid heat of the south.

After an hour, lungs choking and heads thumping from Bangalore’s pollution, we started to reverse the trend of increasing chaos and slowly began to shed more and more traffic until we found ourselves on the relatively benign dual carriage-way on the outskirts of town. At the first opportunity we unceremoniously dumped our bikes outside a dhaba and celebrated by treating ourselves to a masala dosa for breakfast. A masala dosa is a thin, usually pancake shaped, breakfast, made from rice and black lentils and stuffed with spicy potatoes. Dipped in sambar and chutney they are the South Indian equivalent of a hearty breakfast and they were to become a morning ritual.

After an hour, lungs choking and heads thumping from Bangalore’s pollution, we started to reverse the trend of increasing chaos and slowly began to shed more and more traffic until we found ourselves on the relatively benign dual carriage-way on the outskirts of town. At the first opportunity we unceremoniously dumped our bikes outside a dhaba and celebrated by treating ourselves to a masala dosa for breakfast. A masala dosa is a thin, usually pancake shaped, breakfast, made from rice and black lentils and stuffed with spicy potatoes. Dipped in sambar and chutney they are the South Indian equivalent of a hearty breakfast and they were to become a morning ritual.

By the time we were ready to hit the road once more, the early morning stress had long since dissipated into the air along with several thousand tons of traffic fumes and a masala dosa induced sweat. We were ready to experience life on the road in India and, bubbling in each other’s company, we set off to see what would happen. We swept past limestone outcrops, coconut and sugar plantations and, to remind us that we had just spent the best part of a week in India’s richest city, amusement parks and golf courses.

I relished being on the move like this. There was an overriding plan, of course, to head to the southern tip of India. And within this plan were many smaller destinations, but they were mostly destinations and finite entities, and as there were expectations with these destinations, they were inevitably sullied and spoiled by my imagination. The real trip was the journey to get there, the unexpected encounters where eventualities were impossible to predict and the possibilities were infinite. I could never be disappointed with something I had never thought of, and India was full of them. The sight of a camel being led down the road, a thumbs up from a motorcyclist, the passing of a tiny parade, the shade of the bayan tree, and the cheering of boys playing cricket in the nearby field. This was India at its rawest and its best, and also at its most unpredictable.

We bumped into a colourful Hindu procession while cycling through a small village. The men wore black lunghis, yellow turbans and yellow tassels tied to their biceps. The women, in an explosion of colour, wore their best saris and on their heads offerings of incense, fruit and cocktail umbrellas. They all turned towards us and greeted us with inquisitive smiles. The same festival may have been occurring annually for millennia, Hindu civilisation being the only classical culture to survive intact from the ancient world, although I sense the cocktail umbrellas may have been a modern addition.

As the days wore on and we headed further south, it actually become surprisingly cool. So cool in fact it was officially a “cold spell”. Temperatures plummeted to the ‘coldest of the last decade’ according to the local paper. Doctors were reporting an increase in respiratory problems and occurrences of the common cold were soaring. Temperatures had plummeted to a whopping low of 10oC! We revelled in the early morning respite. Meanwhile, most of the local population wrapped themselves up in woollen jumpers and thick balaclavas as if they were getting ready for the imminent snow or bank heist. By 10 o’clock the mercury usually rose to above 30oC, and it was still rising as we threaded our way through the streets of the provincial capital Mysore late one afternoon.

That evening we dined at the Parkland Hotel where on the menu we were informed “Disposable vomit bags are available on request in case of need, as a consideration to fellow diners”. Astonishingly, we actually stayed and ate. No vomit bags were needed.

The ‘cold spell’ continued and the next day we rose early to make the most of it. Ahead lay the Western Ghats. The Western Ghats act as a barrier in Southern India, separating the steep hillsides of the west from the broad Deccan Plateau on the east, and form the geological spine of a catchment system that drains to nearly half of India’s low lying area, providing water, and with it life, to its inhabitants.

The road twisted and turned and rose over ever heightening humps, like crenulations dissipating out from the approaching Ghats. Bayan trees lined the road offering shade and respite, their roots twisted and contorted like manacles fixing the tree to the ground, lest it should uproot and run away, while others simply hung downwards like fishing lines, waiting to catch their passing prey. Coconut wallahs were plentiful and we shed ourselves of small change every hour, sucking the cool refreshing juices through a straw and if we were lucky enough, the limp moist flesh from its innards. As everywhere in India, there were always people and they greeted us friendlily, sometimes excitedly, like we were celebrities passing through their lives. On every corner and bridge, at every chai shop and adobe house, we ‘celebrities’ rolled through their lives, attracting smiles as souvenirs, before heading on our way.

From the crest of a hill, we free-wheeled down the narrow road to the border post at Bandipur National Park. For the first time since Nepal the forest began to close in around us, the rich montane forest oozed peacefulness, shade and a rich green curtain of solitude. One of the last frontiers for the Asian Elephant, we were unsure whether we would be allowed to enter to the park on bicycles. A large articulated barrier blocked the way and we slowed to a halt. A couple of bored looking Rangers sauntered out of the small hut on the side of the road, eyed us interestedly, and gestured us to stop. The more senior looking ranger spoke. He had a demanding manner that matched his place of authority. Just as he was about to order us back to where we came from, his manner changed to that of a whimpering school boy and he rather meekly suggested that we might be inclined to give him and his friend a “Pen?” Tina and I, expecting to be halted in our tracks, merely burst out laughing, ducked under the now raising barrier and sped off into elephant country before he could even think about changing his mind, and before we had a chance to dwell on any misgivings of our sanity.

Enjoying it was easy. For the first time since arriving in India there was peace and solitude. The odd truck or car whizzed past but gone were the houses, the workers, the random road wanderers, the screaming children, the staring villagers, the road side vendors, and the vast acres of flat cultivated fields. It wasn’t a quiet peace, birds called and darted above the tree tops, monkeys swung noisily from branch to branch, and the deafening sound of cicadas, not the chirp of your average cicada, rather the long high pitched, high decibel, ear piercing sound of the chibre, reverberated from all directions. Despite the noise, it was idyllic all the same.

Our destination that day was the small town of Masunigudi, where Karpa, a good friend of ours, was studying elephant behaviour. We were to spend a week in Masunigudi, recharging our batteries before the final push south. India was a truly amazing country to cycle in, but it drained our ‘batteries’ like I have never felt before. It was always a relief to arrive somewhere quiet and put some roots down for a few days before we pushed on. However, the allure of the road and the unpredictable was always close, and it was with these apposing forces (to stop and to go) that we leap-frogged our way down the coast to Kanykamurai – the southern tip of India, over the next few weeks. The Hero, as ever, performed flawlessly.

The Nitty Gritty:

India is definitely not the easiest cycling destination in the world, with horrific roads and suicidal drivers (a bit like New Zealand), constant in-your-face poverty which makes you wonder why we ever complain about anything, and little in the way of idyllic camp spots (particularly outside the mountainous north). However, the people are incredibly friendly and welcoming, the food is fantastic and cheap, the accommodation is… well it’s cheap, and without a doubt it would have to be the most culturally colourful destination I have ever been to. It pays to check out the weather stats before you go as the continent is subject to a complex alpine, monsoonal and tropical climate. Our trip was undertaken from October to January from north to south which seemed to avoid the worst of the cold and heat; I wouldn’t have missed out on the monsoonal downpours in the south for anything! The bikes are cheap too as well as being bullet proof. I clocked up a tad over 3000 km on the Hero, pumping the tyres up twice, and tightened a few bolts up after they rattled loose. I even followed the locals lead and allowed my chain to turn golden with rust. The bike was no worse for wear. After a dousing of monsoonal rain, it gleamed like the day I had bought it.

(First published Groundeffect Underground Newsletter August 2011, http://www.groundeffect.co.nz/oldblog/hotrides/?id=78)